Understanding Sacred Space and Holiness

Understanding Sacred Space and Holiness: What It Means to Be Set Apart

In the ancient world, the distinction between sacred and ordinary space wasn't just a religious concept—it was fundamental to how people understood reality itself. For the Israelites, this understanding shaped their entire identity as God's chosen people.

What Does It Mean to Be God's Portion?

The story begins with God's dramatic decision at Babel. When the nations refused to spread across the earth as commanded, choosing instead to build a tower and stay together, God made a radical choice. He disinherited all the nations and placed them under the authority of lesser spiritual beings. But from this judgment came a promise—God would start over with one man: Abraham.

Through Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (later renamed Israel), God was creating a people who would be His portion on earth. They existed not by natural means, but because God supernaturally enabled Isaac's birth and preserved them through miraculous intervention.

Why Does Holiness Matter?

Holiness Means Being Different

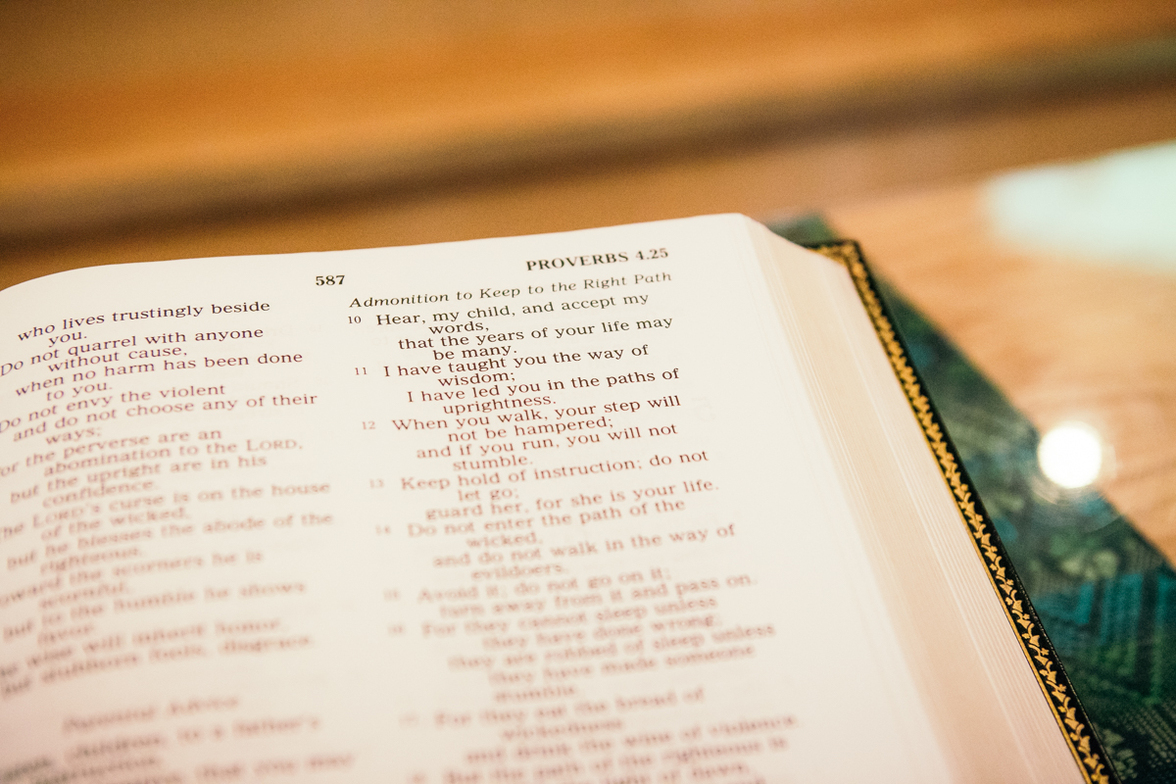

When we hear the word "holy," we often think about moral perfection. But the Hebrew concept of holiness primarily means "otherness" or being set apart. When Leviticus 19:2 commands the Israelites to "be holy as God is holy," it's not primarily about moral behavior—it's about being distinct from the world around them.

This distinction should be visible. People should be able to look at Christians and recognize that we are different. We live by different values, pursue different goals, and find our identity in something beyond this world.

The Problem with Blending In

Today's church often struggles with maintaining this distinctiveness. When churches offer practices like "Christian yoga" or when believers live indistinguishably from the world around them, we lose something essential to our identity. The goal isn't to be weird for the sake of being weird, but to maintain our connection to the sacred in a profane world.

How Did the Tabernacle Teach About Sacred Space?

Gradations of Holiness

The tabernacle wasn't just a tent—it was a carefully designed object lesson about approaching God. As you moved from the outer court toward the holy of holies, the space became progressively more sacred. Different levels required different preparations and different clothing.

The high priest, who alone could enter the most sacred space, wore bells and had a rope tied around his ankle. If the bells stopped ringing, it meant he wasn't holy enough to survive God's presence, and they could drag his body out. Imagine the fear and reverence that would inspire!

Heaven on Earth

The tabernacle was designed to be a copy of heaven—a place where heaven and earth intersected. Like Eden before it, this was where God chose to dwell among His people. The design elements weren't arbitrary; they connected back to the Garden of Eden in multiple ways:

- Both were entered from the east

- Both contained gold, bdellium, and onyx stone

- Both featured cherubim guarding God's presence

- Both represented the meeting place of divine and human realms

What Was the Day of Atonement Really About?

Two Goats, Two Destinations

One of the most misunderstood rituals in Scripture involves two goats on the Day of Atonement. One goat was sacrificed to the Lord, but the other was sent to "Azazel"—not just "the scapegoat" as many translations suggest, but to a specific spiritual being.

Recent scholarship, aided by discoveries like the Dead Sea Scrolls, reveals that Azazel was understood to be a demonic entity, likely one of the fallen angels from Genesis 6. The ritual wasn't about paying a ransom to evil forces, but about putting sin where it belongs—outside of God's holy space, in the realm of chaos and evil.

Realm Distinction in Action

This ceremony powerfully illustrated the concept of realm distinction. Sin couldn't remain in the presence of the holy God, so it was symbolically transported to where evil belonged—outside the camp, in the wilderness, in the domain of hostile spiritual forces.

What Happened When Jesus Went to the Wilderness?

Understanding this background gives new meaning to Jesus' 40 days in the wilderness. He wasn't just going to a quiet place to pray—He was entering enemy territory, the realm associated with chaos and evil spirits. His victory there was a direct confrontation with the forces that had been given dominion over the disinherited nations.

How Should This Change How We Live?

We Are the Temple Now

The church building isn't the temple—we are. This means the distinction between sacred and ordinary should be lived out in our daily lives, not just observed in religious buildings. The same God who required careful preparation to enter His presence now dwells within believers.

Called to Be Different

Just as Israel was called to be a kingdom of priests, standing between God and the nations, Christians are called to make God's name known. This requires maintaining our distinctiveness while engaging with the world around us.

Life Application

This week, examine your life for areas where you've lost the distinction between sacred and ordinary. Are you living in a way that reflects your identity as God's portion, or have you blended so completely with the world that no one can tell the difference?

Consider these questions:

- In what areas of my life am I indistinguishable from non-believers?

- How can I maintain healthy separation from worldly values while still engaging with people who need to know God?

- What practices or habits do I need to change to better reflect my identity as someone set apart for God's purposes?

- Am I fulfilling my calling to be a priest—someone who stands between God and others to make His name known?

The goal isn't to become isolated or judgmental, but to live with such clarity about your identity in Christ that others are drawn to ask about the hope you have. Your distinctiveness should point people toward God, not away from Him